Federal health official: Community collaboration key in cutting overdose deaths and addiction

Anthony C. Ferreri, the regional director of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), toured Catholic Charities, Diocese of Trenton’s ambulatory detox facility in Trenton today. He applauded the integrative program as a model of community collaboration that can be replicated to reduce overdose deaths and addiction overall.

Ferreri (pictured, right) discussed the catastrophic scale of the opioid epidemic, noting that New Jersey – where more than 2,000 people have fatally overdosed so far this year – has one of the fastest growing overdose rates in the nation. He also discussed strategies communities should use to fight the crisis and praised the Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinic (CCBHC) program in practice at Catholic Charities as a success.

He met leaders from Catholic Charities and its community partners, including Capital Health, HomeFront, the Rescue Mission of Trenton, and Rapp’s Pharmacy.

Cooperation key

He specifically lauded the community collaboration that’s key to CCBHCs, a new federal model of care intended to strengthen community-based healthcare services for those whose complex needs have historically left them out of the system.

One of Catholic Charities’ CCBHC programs, for example, is For My Baby and Me. Six community groups – Catholic Charities, Capital Health, the Rescue Mission of Trenton, the Trenton Health Team, the Henry J. Austin Health Center, and HomeFront – coordinate care in that program to holistically serve pregnant women struggling with addiction who are homeless or at risk of becoming homeless.

Expansion planned

Ferreri’s visit comes two weeks after HHS awarded Catholic Charities $4 million to expand its CCBHC. The new funding will empower Catholic Charities to remove barriers to treatment for scores more people struggling to overcome addiction, said Marlene Laó-Collins, Catholic Charities executive director (pictured, right).

“This new funding has enabled us to partner with other community groups and break down the ‘silos’ of care, so that we are able to help people not only recover, but to also to move on with their lives – to get housing, to get employment, to finish their schooling, to do any number of things you need to not only survive but thrive,” Laó-Collins said. “It takes a whole village of people to make this work. We all are working together to serve the community better.”

A success story

Ferreri also heard from a new mother, Sabrina, who joined For My Baby and Me last spring. She alternately smiled and teared up as she talked about finding sobriety and stability after years of addiction. She had her baby, Alyssa, in August and now has plans to get married.

Ferreri also heard from a new mother, Sabrina, who joined For My Baby and Me last spring. She alternately smiled and teared up as she talked about finding sobriety and stability after years of addiction. She had her baby, Alyssa, in August and now has plans to get married.

“I brought my baby home, which was the greatest thing I could have imagined. We are hopefully going to be getting our own place, with the help of the program. I really don’t know what I would have done if my family hadn’t found this program. They’ve been so supportive, there for us every step of the way,” said Sabrina (pictured, left). “If this grant wasn’t here with this program, with all this support I’ve received here, I’d probably be dead, especially with all the fentanyl out there.”

As Alyssa stirred in her baby stroller, Sabrina caressed her and continued: “This is just the greatest program. They have a great staff. I know I did most of the work, but if it wasn’t for everybody’s help, I wouldn’t have her. And she’s awesome.”

Calamitous cost

During his visit, Ferreri outlined the devastating scale of the opioid crisis, as well as the government’s strategy in combatting it, in a slide presentation and subsequent roundtable discussion.

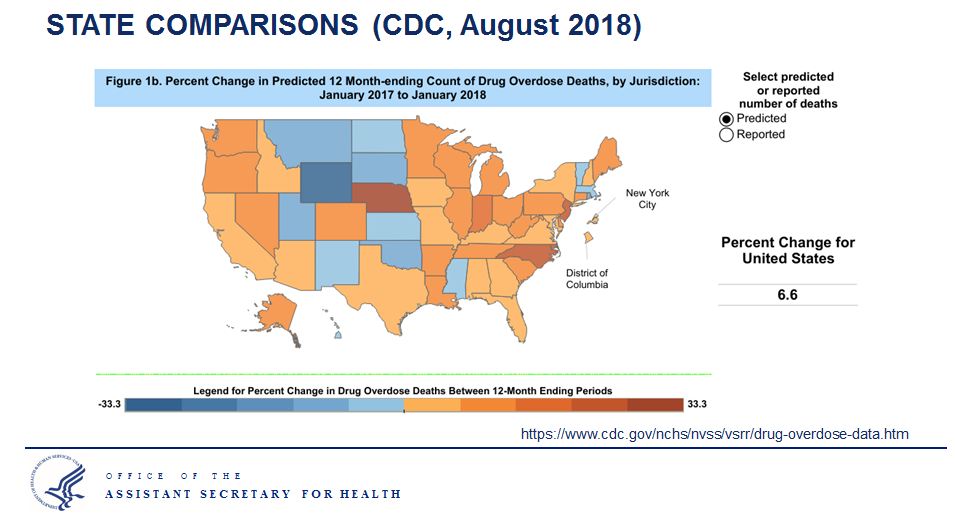

Drug overdose deaths continue to climb, with more than 71,500 people fatally overdosing in 2017, a 6.6 percent increase over the previous year, Ferreri said. Drug use starts early, for many, with one in seven U.S. high school students reporting that they misuse opioids, Ferreri said.

Meanwhile, opioids continue to be the deadliest drug among substance users, outpacing heroin, methadone and natural and semi-synthetic opioids by far in mortality measures. Fatal opioid overdoses affect all age groups, spiking highest among those age 25 to 34.

New Jersey, in particular, fares worse than most states, when it comes reducing overdose deaths, Ferreri added. (State data shows 2,080 fatal overdoses statewide this year, through Sept. 17.) Only Nebraska and North Carolina have seen their percentage of overdose deaths rise as fast as New Jersey did in 2017, said Ferreri, citing data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control.

New Jersey, in particular, fares worse than most states, when it comes reducing overdose deaths, Ferreri added. (State data shows 2,080 fatal overdoses statewide this year, through Sept. 17.) Only Nebraska and North Carolina have seen their percentage of overdose deaths rise as fast as New Jersey did in 2017, said Ferreri, citing data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control.

“This was once a disease that affected people of lower economic means,” Ferreri said. “This now is a disease that has moved into the living rooms of middle-class America. This is a disease that is killing people at all levels of the economic stratosphere.”

Far-reaching impact

In addition, the crisis has had a catastrophic effect on the U.S. economy, he said. The White House’s Council of Economic Advisers estimated in a November 2017 report that the epidemic, when you weigh the staggering number of lives lost, cost the country $504 billion in 2015 alone.

Beyond fatalities, drug use has infectious consequences, Ferreri said, driving up rates of HIV, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, endocarditis, and skin, bone and joint infections. And the number of babies born with neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), which can lead to premature birth, low birthweight and lifelong developmental disorders, has climbed steadily since 2008, he added.

Law enforcement plays a vital role in reducing the illegal importation of fentanyl and other deadly substances, Ferreri said. In May, for example, state troopers stopped a truck in Nebraska that contained 118 pounds of fentanyl – enough to kill more than 26 million people, Ferreri said. It was the largest fentanyl seizure in state history, and one of the largest in the United States.

A strategy to fight the crisis

Otherwise, HHS has a five-point strategy in reducing opioid deaths and addiction, Ferreri said.

- Strengthen public health data collection and reporting.

- Advance the practice of pain management to cut inappropriate use of opioids.

- Improve access to prevention, treatment, and recovery services.

- Enhance the availability of overdose-reversing medications like naloxone.

- Support cutting-edge research on pain and addiction, which could lead to new treatments and identify effective public-health interventions.

Ferreri praised other effective, evidence-based strategies for fighting the epidemic, including targeted naloxone distribution; medication-assisted treatment (MAT) including initiating it in hospital emergency rooms; 911 Good Samaritan laws that protect people who report overdoses from prosecution; testing for fentanyl in routine toxicology testing; increased focus on naloxone and MAT (treating addiction as disease instead of crime) in criminal justice settings; and syringe services programs (such as safe-injection sites and needle-exchange programs).

He said the government is working to integrate and improve recovery treatment programs in highly stricken communities and reduce barriers in rural communities. President Trump’s 2019 budget includes more than $3 billion for state-targeted grants, rural health initiatives, community health centers, CDC surveillance, and pain- and opioid-related scientific research, Ferreri said.

Housing a concern

At a roundtable discussion after his tour, community leaders told Ferreri affordable housing continues to be a challenging hurdle for many recovering from drug addiction.

New Jersey is one of the most expensive states in the nation to rent, buy or build. People struggling with addiction can remain mired in poverty or otherwise have financial difficulties, so stable, affordable housing can be elusive. Ferreri pledged to connect the community leaders with federal housing officials to work on ways to expand affordable housing opportunities for people in recovery.

New Jersey ties

The Trump administration appointed Ferreri in June to head the Department’s Region II, which encompasses New Jersey, New York, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and eight Tribal nations. He reports to HHS Secretary Alex M. Azar II and works with state and local governments and organizations to advance HHS priorities.

Ferreri is a Rutgers University graduate who spent 40 years in the healthcare industry, including in leadership positions at Staten Island University Hospital, Northwell Health System in New York, and St. Barnabas Medical Center in Livingston, NJ.

Further reading: HHS offers an Opioid Epidemic Practical Toolkit with strategies for community and faith-based leaders to reduce overdose deaths and heal communities. See it by clicking here.

For help: Call our Access, Help and Information Center at (800) 360-7711 to connect with our professional staff for addiction recovery.

To subscribe to our blog posts and news releases, fill out the fields below.